11.6 The Hall Effect

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain a scenario where the magnetic and electric fields are crossed and their forces balance each other as a charged particle moves through a velocity selector

- Compare how charge carriers move in a conductive material and explain how this relates to the Hall effect

In 1879, E.H. Hall devised an experiment that can be used to identify the sign of the predominant charge carriers in a conducting material. From a historical perspective, this experiment was the first to demonstrate that the charge carriers in most metals are negative.

Interactive

Visit this website to find more information about the Hall effect.

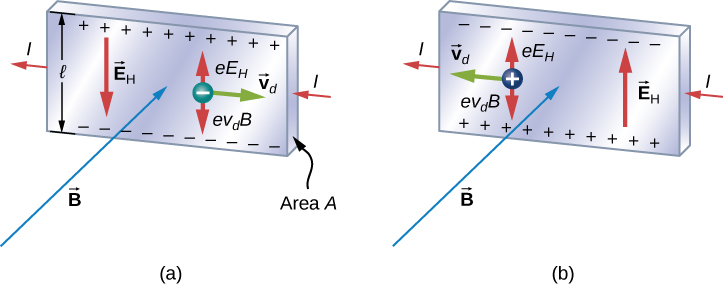

We investigate the Hall effect by studying the motion of the free electrons along a metallic strip of width l in a constant magnetic field (Figure 11.17). The electrons are moving from left to right, so the magnetic force they experience pushes them to the bottom edge of the strip. This leaves an excess of positive charge at the top edge of the strip, resulting in an electric field E directed from top to bottom. The charge concentration at both edges builds up until the electric force on the electrons in one direction is balanced by the magnetic force on them in the opposite direction. Equilibrium is reached when:

where e is the magnitude of the electron charge, is the drift speed of the electrons, and E is the magnitude of the electric field created by the separated charge. Solving this for the drift speed results in

A scenario where the electric and magnetic fields are perpendicular to one another is called a crossed-field situation. If these fields produce equal and opposite forces on a charged particle with the velocity that equates the forces, these particles are able to pass through an apparatus, called a velocity selector, undeflected. This velocity is represented in Equation 11.25. Any other velocity of a charged particle sent into the same fields would be deflected by the magnetic force or electric force.

Going back to the Hall effect, if the current in the strip is I, then from Current and Resistance, we know that

where n is the number of charge carriers per volume and A is the cross-sectional area of the strip. Combining the equations for and I results in

The field E is related to the potential difference V between the edges of the strip by

The quantity V is called the Hall potential and can be measured with a voltmeter. Finally, combining the equations for I and E gives us

where the upper edge of the strip in Figure 11.17 is positive with respect to the lower edge.

We can also combine Equation 11.24 and Equation 11.28 to get an expression for the Hall voltage in terms of the magnetic field:

What if the charge carriers are positive, as in Figure 11.17? For the same current I, the magnitude of V is still given by Equation 11.29. However, the upper edge is now negative with respect to the lower edge. Therefore, by simply measuring the sign of V, we can determine the sign of the majority charge carriers in a metal.

Hall potential measurements show that electrons are the dominant charge carriers in most metals. However, Hall potentials indicate that for a few metals, such as tungsten, beryllium, and many semiconductors, the majority of charge carriers are positive. It turns out that conduction by positive charge is caused by the migration of missing electron sites (called holes) on ions. Conduction by holes is studied later in Condensed Matter Physics.

The Hall effect can be used to measure magnetic fields. If a material with a known density of charge carriers n is placed in a magnetic field and V is measured, then the field can be determined from Equation 11.29. In research laboratories where the fields of electromagnets used for precise measurements have to be extremely steady, a “Hall probe” is commonly used as part of an electronic circuit that regulates the field.

Example 11.8

Velocity Selector

An electron beam enters a crossed-field velocity selector with magnetic and electric fields of 2.0 mT and respectively. (a) What must the velocity of the electron beam be to traverse the crossed fields undeflected? If the electric field is turned off, (b) what is the acceleration of the electron beam and (c) what is the radius of the circular motion that results?Strategy

The electron beam is not deflected by either of the magnetic or electric fields if these forces are balanced. Based on these balanced forces, we calculate the velocity of the beam. Without the electric field, only the magnetic force is used in Newton’s second law to find the acceleration. Lastly, the radius of the path is based on the resulting circular motion from the magnetic force.Solution

- The velocity of the unperturbed beam of electrons with crossed fields is calculated by Equation 11.25:

- The acceleration is calculated from the net force from the magnetic field, equal to mass times acceleration. The magnitude of the acceleration is:

- The radius of the path comes from a balance of the circular and magnetic forces, or Equation 11.25:

Significance

If electrons in the beam had velocities above or below the answer in part (a), those electrons would have a stronger net force exerted by either the magnetic or electric field. Therefore, only those electrons at this specific velocity would make it through.Example 11.9

The Hall Potential in a Silver Ribbon

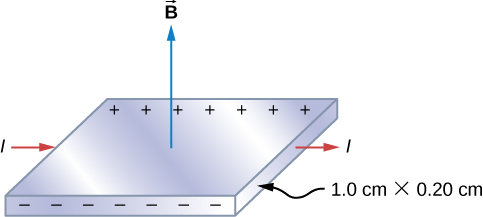

Figure 11.18 shows a silver ribbon whose cross section is 1.0 cm by 0.20 cm. The ribbon carries a current of 100 A from left to right, and it lies in a uniform magnetic field of magnitude 1.5 T. Using a density value of electrons per cubic meter for silver, find the Hall potential between the edges of the ribbon.

Strategy

Since the majority of charge carriers are electrons, the polarity of the Hall voltage is that indicated in the figure. The value of the Hall voltage is calculated using Equation 11.29:Solution

When calculating the Hall voltage, we need to know the current through the material, the magnetic field, the length, the number of charge carriers, and the area. Since all of these are given, the Hall voltage is calculated as:Significance

As in this example, the Hall potential is generally very small, and careful experimentation with sensitive equipment is required for its measurement.Check Your Understanding 11.5

A Hall probe consists of a copper strip, electrons per cubic meter, which is 2.0 cm wide and 0.10 cm thick. What is the magnetic field when I = 50 A and the Hall potential is (a) and (b)