1.3 Refraction

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe how rays change direction upon entering a medium

- Apply the law of refraction in problem solving

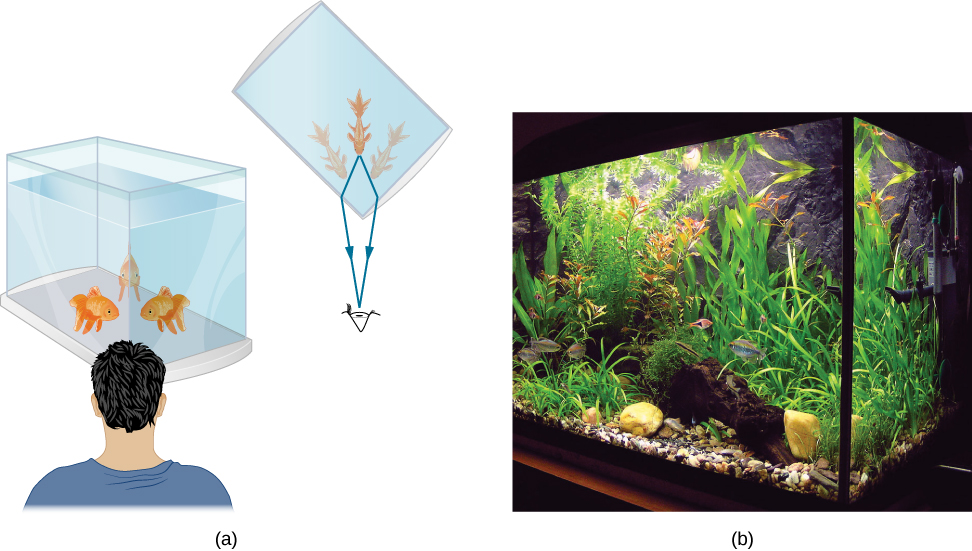

You may often notice some odd things when looking into a fish tank. For example, you may see the same fish appearing to be in two different places (Figure 1.12). This happens because light coming from the fish to you changes direction when it leaves the tank, and in this case, it can travel two different paths to get to your eyes. The changing of a light ray’s direction (loosely called bending) when it passes through substances of different refractive indices is called refraction and is related to changes in the speed of light, . Refraction is responsible for a tremendous range of optical phenomena, from the action of lenses to data transmission through optical fibers.

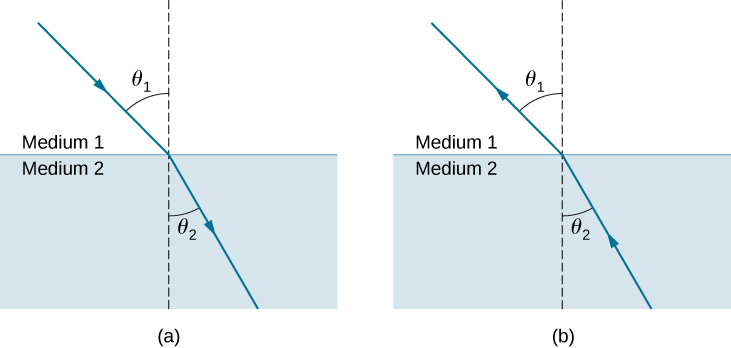

Figure 1.13 shows how a ray of light changes direction when it passes from one medium to another. As before, the angles are measured relative to a perpendicular to the surface at the point where the light ray crosses it. (Some of the incident light is reflected from the surface, but for now we concentrate on the light that is transmitted.) The change in direction of the light ray depends on the relative values of the indices of refraction (The Propagation of Light) of the two media involved. In the situations shown, medium 2 has a greater index of refraction than medium 1. Note that as shown in Figure 1.13(a), the direction of the ray moves closer to the perpendicular when it progresses from a medium with a lower index of refraction to one with a higher index of refraction. Conversely, as shown in Figure 1.13(b), the direction of the ray moves away from the perpendicular when it progresses from a medium with a higher index of refraction to one with a lower index of refraction. The path is exactly reversible.

The amount that a light ray changes its direction depends both on the incident angle and the amount that the speed changes. For a ray at a given incident angle, a large change in speed causes a large change in direction and thus a large change in angle. The exact mathematical relationship is the law of refraction, or Snell’s law, after the Dutch mathematician Willebrord Snell (1591–1626), who discovered it in 1621. While the law has been named after Snell, the Arabian physicist Ibn Sahl found the law of refraction in 984 and used it in his work On Burning Mirrors and Lenses. The law of refraction is stated in equation form as

Here and are the indices of refraction for media 1 and 2, and and are the angles between the rays and the perpendicular in media 1 and 2. The incoming ray is called the incident ray, the outgoing ray is called the refracted ray, and the associated angles are the incident angle and the refracted angle, respectively.

Snell’s experiments showed that the law of refraction is obeyed and that a characteristic index of refraction n could be assigned to a given medium and its value measured. Snell was not aware that the speed of light varied in different media, a key fact used when we derive the law of refraction theoretically using Huygens’s principle in Huygens’s Principle.

Example 1.2

Determining the Index of Refraction

Find the index of refraction for medium 2 in Figure 1.13(a), assuming medium 1 is air and given that the incident angle is and the angle of refraction is .Strategy

The index of refraction for air is taken to be 1 in most cases (and up to four significant figures, it is 1.000). Thus, here. From the given information, and With this information, the only unknown in Snell’s law is so we can use Snell’s law to find it.Solution

From Snell’s law we haveEntering known values,

Significance

This is the index of refraction for water, and Snell could have determined it by measuring the angles and performing this calculation. He would then have found 1.33 to be the appropriate index of refraction for water in all other situations, such as when a ray passes from water to glass. Today, we can verify that the index of refraction is related to the speed of light in a medium by measuring that speed directly.Interactive

Engage this Phet simulation between two media with different indices of refraction. Use the “Intro” simulation and see how changing from air to water to glass changes the bending angle. Use the protractor tool to measure the angles and see if you can recreate the configuration in Example 1.2. Also by measurement, confirm that the angle of reflection equals the angle of incidence.

Example 1.3

A Larger Change in Direction

Suppose that in a situation like that in Example 1.2, light goes from air to diamond and that the incident angle is . Calculate the angle of refraction in the diamond.Strategy

Again, the index of refraction for air is taken to be , and we are given . We can look up the index of refraction for diamond in Table 1.1, finding . The only unknown in Snell’s law is , which we wish to determine.Solution

Solving Snell’s law for yieldsEntering known values,

The angle is thus

Significance

For the same angle of incidence, the angle of refraction in diamond is significantly smaller than in water rather than —see Example 1.2). This means there is a larger change in direction in diamond. The cause of a large change in direction is a large change in the index of refraction (or speed). In general, the larger the change in speed, the greater the effect on the direction of the ray.Check Your Understanding 1.2

In Table 1.1, the solid with the next highest index of refraction after diamond is zircon. If the diamond in Example 1.3 were replaced with a piece of zircon, what would be the new angle of refraction?