6.5 De Broglie’s Matter Waves

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe de Broglie’s hypothesis of matter waves

- Explain how the de Broglie’s hypothesis gives the rationale for the quantization of angular momentum in Bohr’s quantum theory of the hydrogen atom

- Describe the Davisson–Germer experiment

- Interpret de Broglie’s idea of matter waves and how they account for electron diffraction phenomena

Compton’s formula established that an electromagnetic wave can behave like a particle of light when interacting with matter. In 1924, Louis de Broglie proposed a new speculative hypothesis that electrons and other particles of matter can behave like waves. Today, this idea is known as de Broglie’s hypothesis of matter waves. In 1926, De Broglie’s hypothesis, together with Bohr’s early quantum theory, led to the development of a new theory of wave quantum mechanics to describe the physics of atoms and subatomic particles. Quantum mechanics has paved the way for new engineering inventions and technologies, such as the laser and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These new technologies drive discoveries in other sciences such as biology and chemistry.

According to de Broglie’s hypothesis, massless photons as well as massive particles must satisfy one common set of relations that connect the energy E with the frequency f, and the linear momentum p with the wavelength We have discussed these relations for photons in the context of Compton’s effect. We are recalling them now in a more general context. Any particle that has energy and momentum is a de Broglie wave of frequency f and wavelength

Here, E and p are, respectively, the relativistic energy and the momentum of a particle. De Broglie’s relations are usually expressed in terms of the wave vector and the wave frequency as we usually do for waves:

Wave theory tells us that a wave carries its energy with the group velocity. For matter waves, this group velocity is the velocity u of the particle. Identifying the energy E and momentum p of a particle with its relativistic energy and its relativistic momentum mu, respectively, it follows from de Broglie relations that matter waves satisfy the following relation:

where When a particle is massless we have and Equation 6.57 becomes

Example 6.11

How Long Are de Broglie Matter Waves?

Calculate the de Broglie wavelength of: (a) a 0.65-kg basketball thrown at a speed of 10 m/s, (b) a nonrelativistic electron with a kinetic energy of 1.0 eV, and (c) a relativistic electron with a kinetic energy ofStrategy

We use Equation 6.57 to find the de Broglie wavelength. When the problem involves a nonrelativistic object moving with a nonrelativistic speed u, such as in (a) when we use nonrelativistic momentum p. When the nonrelativistic approximation cannot be used, such as in (c), we must use the relativistic momentum where the rest mass energy of a particle is and is the Lorentz factor The total energy E of a particle is given by Equation 6.53 and the kinetic energy is When the kinetic energy is known, we can invert Equation 6.18 to find the momentum and substitute in Equation 6.57 to obtainDepending on the problem at hand, in this equation we can use the following values for hc:

Solution

- For the basketball, the kinetic energy is and the rest mass energy is We see that and use

- For the nonrelativistic electron, and when we have so we can use the nonrelativistic formula. However, it is simpler here to use Equation 6.58: If we use nonrelativistic momentum, we obtain the same result because 1 eV is much smaller than the rest mass of the electron.

- For a fast electron with relativistic effects cannot be neglected because its total energy is and is not negligible:

Significance

We see from these estimates that De Broglie’s wavelengths of macroscopic objects such as a ball are immeasurably small. Therefore, even if they exist, they are not detectable and do not affect the motion of macroscopic objects.Check Your Understanding 6.11

What is de Broglie’s wavelength of a nonrelativistic proton with a kinetic energy of 1.0 eV?

Using the concept of the electron matter wave, de Broglie provided a rationale for the quantization of the electron’s angular momentum in the hydrogen atom, which was postulated in Bohr’s quantum theory. The physical explanation for the first Bohr quantization condition comes naturally when we assume that an electron in a hydrogen atom behaves not like a particle but like a wave. To see it clearly, imagine a stretched guitar string that is clamped at both ends and vibrates in one of its normal modes. If the length of the string is l (Figure 6.18), the wavelengths of these vibrations cannot be arbitrary but must be such that an integer k number of half-wavelengths fit exactly on the distance l between the ends. This is the condition for a standing wave on a string. Now suppose that instead of having the string clamped at the walls, we bend its length into a circle and fasten its ends to each other. This produces a circular string that vibrates in normal modes, satisfying the same standing-wave condition, but the number of half-wavelengths must now be an even number and the length l is now connected to the radius of the circle. This means that the radii are not arbitrary but must satisfy the following standing-wave condition:

If an electron in the nth Bohr orbit moves as a wave, by Equation 6.59 its wavelength must be equal to Assuming that Equation 6.58 is valid, the electron wave of this wavelength corresponds to the electron’s linear momentum, In a circular orbit, therefore, the electron’s angular momentum must be

This equation is the first of Bohr’s quantization conditions, given by Equation 6.36. Providing a physical explanation for Bohr’s quantization condition is a convincing theoretical argument for the existence of matter waves.

Example 6.12

The Electron Wave in the Ground State of Hydrogen

Find the de Broglie wavelength of an electron in the ground state of hydrogen.Strategy

We combine the first quantization condition in Equation 6.60 with Equation 6.36 and use Equation 6.38 for the first Bohr radius withSolution

When and the Bohr quantization condition gives The electron wavelength is:Significance

We obtain the same result when we use Equation 6.58 directly.Check Your Understanding 6.12

Find the de Broglie wavelength of an electron in the third excited state of hydrogen.

Experimental confirmation of matter waves came in 1927 when C. Davisson and L. Germer performed a series of electron-scattering experiments that clearly showed that electrons do behave like waves. Davisson and Germer did not set up their experiment to confirm de Broglie’s hypothesis: The confirmation came as a byproduct of their routine experimental studies of metal surfaces under electron bombardment.

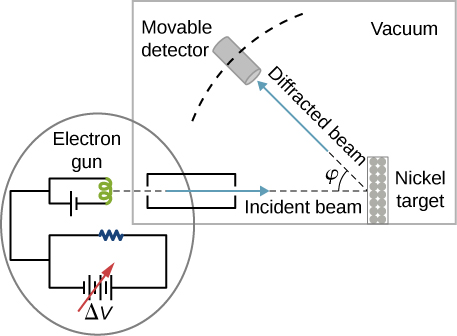

In the particular experiment that provided the very first evidence of electron waves (known today as the Davisson–Germer experiment), they studied a surface of nickel. Their nickel sample was specially prepared in a high-temperature oven to change its usual polycrystalline structure to a form in which large single-crystal domains occupy the volume. Figure 6.19 shows the experimental setup. Thermal electrons are released from a heated element (usually made of tungsten) in the electron gun and accelerated through a potential difference becoming a well-collimated beam of electrons produced by an electron gun. The kinetic energy K of the electrons is adjusted by selecting a value of the potential difference in the electron gun. This produces a beam of electrons with a set value of linear momentum, in accordance with the conservation of energy:

The electron beam is incident on the nickel sample in the direction normal to its surface. At the surface, it scatters in various directions. The intensity of the beam scattered in a selected direction is measured by a highly sensitive detector. The detector’s angular position with respect to the direction of the incident beam can be varied from to The entire setup is enclosed in a vacuum chamber to prevent electron collisions with air molecules, as such thermal collisions would change the electrons’ kinetic energy and are not desirable.

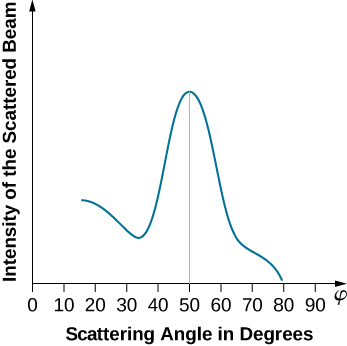

When the nickel target has a polycrystalline form with many randomly oriented microscopic crystals, the incident electrons scatter off its surface in various random directions. As a result, the intensity of the scattered electron beam is much the same in any direction, resembling a diffuse reflection of light from a porous surface. However, when the nickel target has a regular crystalline structure, the intensity of the scattered electron beam shows a clear maximum at a specific angle and the results show a clear diffraction pattern (see Figure 6.20). Similar diffraction patterns formed by X-rays scattered by various crystalline solids were studied in 1912 by father-and-son physicists William H. Bragg and William L. Bragg. The Bragg law in X-ray crystallography provides a connection between the wavelength of the radiation incident on a crystalline lattice, the lattice spacing, and the position of the interference maximum in the diffracted radiation (see Diffraction).

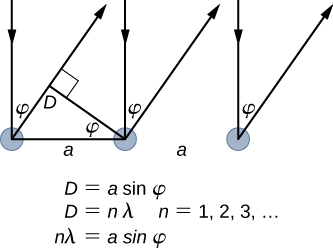

The lattice spacing of the Davisson–Germer target, determined with X-ray crystallography, was measured to be Unlike X-ray crystallography in which X-rays penetrate the sample, in the original Davisson–Germer experiment, only the surface atoms interact with the incident electron beam. For the surface diffraction, the maximum intensity of the reflected electron beam is observed for scattering angles that satisfy the condition (see Figure 6.21). The first-order maximum (for ) is measured at a scattering angle of at which gives the wavelength of the incident radiation as On the other hand, a 54-V potential accelerates the incident electrons to kinetic energies of Their momentum, calculated from Equation 6.61, is When we substitute this result in Equation 6.58, the de Broglie wavelength is obtained as

The same result is obtained when we use in Equation 6.61. The proximity of this theoretical result to the Davisson–Germer experimental value of is a convincing argument for the existence of de Broglie matter waves.

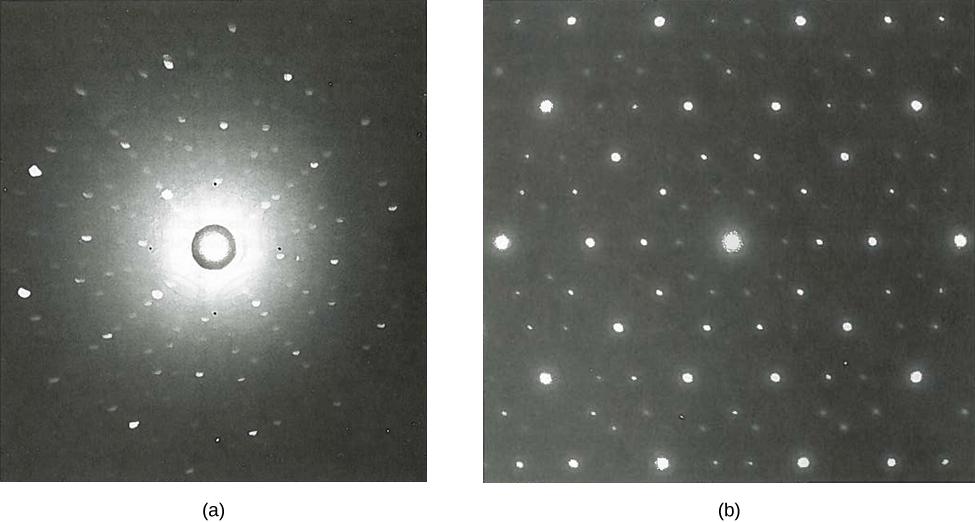

Diffraction lines measured with low-energy electrons, such as those used in the Davisson–Germer experiment, are quite broad (see Figure 6.20) because the incident electrons are scattered only from the surface. The resolution of diffraction images greatly improves when a higher-energy electron beam passes through a thin metal foil. This occurs because the diffraction image is created by scattering off many crystalline planes inside the volume, and the maxima produced in scattering at Bragg angles are sharp (see Figure 6.22).

Since the work of Davisson and Germer, de Broglie’s hypothesis has been extensively tested with various experimental techniques, and the existence of de Broglie waves has been confirmed for numerous elementary particles. Neutrons have been used in scattering experiments to determine crystalline structures of solids from interference patterns formed by neutron matter waves. The neutron has zero charge and its mass is comparable with the mass of a positively charged proton. Both neutrons and protons can be seen as matter waves. Therefore, the property of being a matter wave is not specific to electrically charged particles but is true of all particles in motion. Matter waves of molecules as large as carbon have been measured. All physical objects, small or large, have an associated matter wave as long as they remain in motion. The universal character of de Broglie matter waves is firmly established.

Example 6.13

Neutron Scattering

Suppose that a neutron beam is used in a diffraction experiment on a typical crystalline solid. Estimate the kinetic energy of a neutron (in eV) in the neutron beam and compare it with kinetic energy of an ideal gas in equilibrium at room temperature.Strategy

We assume that a typical crystal spacing a is of the order of 1.0 Å. To observe a diffraction pattern on such a lattice, the neutron wavelength must be on the same order of magnitude as the lattice spacing. We use Equation 6.61 to find the momentum p and kinetic energy K. To compare this energy with the energy of ideal gas in equilibrium at room temperature we use the relation where is the Boltzmann constant.Solution

We evaluate pc to compare it with the neutron’s rest mass energyWe see that so and we can use the nonrelativistic kinetic energy:

Kinetic energy of ideal gas in equilibrium at 300 K is:

We see that these energies are of the same order of magnitude.

Significance

Neutrons with energies in this range, which is typical for an ideal gas at room temperature, are called “thermal neutrons.”Example 6.14

Wavelength of a Relativistic Proton

In a supercollider at CERN, protons can be accelerated to velocities of 0.75c. What are their de Broglie wavelengths at this speed? What are their kinetic energies?Strategy

The rest mass energy of a proton is When the proton’s velocity is known, we have and We obtain the wavelength and kinetic energy K from relativistic relations.Solution

Significance

Notice that because a proton is 1835 times more massive than an electron, if this experiment were performed with electrons, a simple rescaling of these results would give us the electron’s wavelength of and its kinetic energy ofCheck Your Understanding 6.13

Find the de Broglie wavelength and kinetic energy of a free electron that travels at a speed of 0.75c.