10.8 Work and Power for Rotational Motion

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Use the work-energy theorem to analyze rotation to find the work done on a system when it is rotated about a fixed axis for a finite angular displacement

- Solve for the angular velocity of a rotating rigid body using the work-energy theorem

- Find the power delivered to a rotating rigid body given the applied torque and angular velocity

- Summarize the rotational variables and equations and relate them to their translational counterparts

Thus far in the chapter, we have extensively addressed kinematics and dynamics for rotating rigid bodies around a fixed axis. In this final section, we define work and power within the context of rotation about a fixed axis, which has applications to both physics and engineering. The discussion of work and power makes our treatment of rotational motion almost complete, with the exception of rolling motion and angular momentum, which are discussed in Angular Momentum. We begin this section with a treatment of the work-energy theorem for rotation.

Work for Rotational Motion

Now that we have determined how to calculate kinetic energy for rotating rigid bodies, we can proceed with a discussion of the work done on a rigid body rotating about a fixed axis. Figure 10.39 shows a rigid body that has rotated through an angle from A to B while under the influence of a force . The external force is applied to point P, whose position is , and the rigid body is constrained to rotate about a fixed axis that is perpendicular to the page and passes through O. The rotational axis is fixed, so the vector moves in a circle of radius r, and the vector is perpendicular to

From Equation 10.2, we have

Thus,

Note that is zero because is fixed on the rigid body from the origin O to point P. Using the definition of work, we obtain

where we used the identity . Noting that , we arrive at the expression for the rotational work done on a rigid body:

The total work done on a rigid body is the sum of the torques integrated over the angle through which the body rotates. The incremental work is

where we have taken the dot product in Equation 10.27, leaving only torques along the axis of rotation. In a rigid body, all particles rotate through the same angle; thus the work of every external force is equal to the torque times the common incremental angle . The quantity is the net torque on the body due to external forces.

Similarly, we found the kinetic energy of a rigid body rotating around a fixed axis by summing the kinetic energy of each particle that makes up the rigid body. Since the work-energy theorem is valid for each particle, it is valid for the sum of the particles and the entire body.

Work-Energy Theorem for Rotation

The work-energy theorem for a rigid body rotating around a fixed axis is

where

and the rotational work done by a net force rotating a body from point A to point B is

We give a strategy for using this equation when analyzing rotational motion.

Problem-Solving Strategy

Work-Energy Theorem for Rotational Motion

- Identify the forces on the body and draw a free-body diagram. Calculate the torque for each force.

- Calculate the work done during the body’s rotation by every torque.

- Apply the work-energy theorem by equating the net work done on the body to the change in rotational kinetic energy.

Let’s look at two examples and use the work-energy theorem to analyze rotational motion.

Example 10.17

Rotational Work and Energy

A torque is applied to a flywheel that rotates about a fixed axis and has a moment of inertia of . If the flywheel is initially at rest, what is its angular velocity after it has turned through eight revolutions?Strategy

We apply the work-energy theorem. We know from the problem description what the torque is and the angular displacement of the flywheel. Then we can solve for the final angular velocity.Solution

The flywheel turns through eight revolutions, which is radians. The work done by the torque, which is constant and therefore can come outside the integral in Equation 10.30, isWe apply the work-energy theorem:

With , we have

Therefore,

This is the angular velocity of the flywheel after eight revolutions.

Significance

The work-energy theorem provides an efficient way to analyze rotational motion, connecting torque with rotational kinetic energy.Example 10.18

Rotational Work: A Pulley

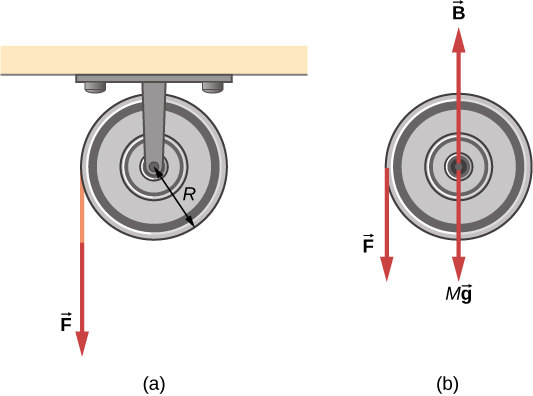

A string wrapped around the pulley in Figure 10.40 is pulled with a constant downward force of magnitude 50 N. The radius R and moment of inertia I of the pulley are 0.10 m and , respectively. If the string does not slip, what is the angular velocity of the pulley after 1.0 m of string has unwound? Assume the pulley starts from rest.

Strategy

Looking at the free-body diagram, we see that neither , the force on the bearings of the pulley, nor, the weight of the pulley, exerts a torque around the rotational axis, and therefore does no work on the pulley. As the pulley rotates through an angle acts through a distance d such thatSolution

Since the torque due to has magnitude , we haveIf the force on the string acts through a distance of 1.0 m, we have, from the work-energy theorem,

Solving for , we obtain

Power for Rotational Motion

Power always comes up in the discussion of applications in engineering and physics. Power for rotational motion is equally as important as power in linear motion and can be derived in a similar way as in linear motion when the force is a constant. The linear power when the force is a constant is . If the net torque is constant over the angular displacement, Equation 10.25 simplifies and the net torque can be taken out of the integral. In the following discussion, we assume the net torque is constant. We can apply the definition of power derived in Power to rotational motion. From Work and Kinetic Energy, the instantaneous power (or just power) is defined as the rate of doing work,

If we have a constant net torque, Equation 10.25 becomes and the power is

or

Example 10.19

Torque on a Boat Propeller

A boat engine operating at is running at 300 rev/min. What is the torque on the propeller shaft?Strategy

We are given the rotation rate in rev/min and the power consumption, so we can easily calculate the torque.Solution

Significance

It is important to note the radian is a dimensionless unit because its definition is the ratio of two lengths. It therefore does not appear in the solution.Check Your Understanding 10.8

A constant torque of is applied to a wind turbine to keep it rotating at 6 rad/s. What is the power required to keep the turbine rotating?

Rotational and Translational Relationships Summarized

The rotational quantities and their linear analog are summarized in three tables. Table 10.5 summarizes the rotational variables for circular motion about a fixed axis with their linear analogs and the connecting equation, except for the centripetal acceleration, which stands by itself. Table 10.6 summarizes the rotational and translational kinematic equations. Table 10.7 summarizes the rotational dynamics equations with their linear analogs.

| Rotational | Translational | Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Rotational | Translational |

|---|---|

| Rotational | Translational |

|---|---|

| m | |