9.3 Resistivity and Resistance

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Differentiate between resistance and resistivity

- Define the term conductivity

- Describe the electrical component known as a resistor

- State the relationship between resistance of a resistor and its length, cross-sectional area, and resistivity

- State the relationship between resistivity and temperature

What drives current? We can think of various devices—such as batteries, generators, wall outlets, and so on—that are necessary to maintain a current. All such devices create a potential difference and are referred to as voltage sources. When a voltage source is connected to a conductor, it applies a potential difference V that creates an electrical field. The electrical field, in turn, exerts force on free charges, causing current. The amount of current depends not only on the magnitude of the voltage, but also on the characteristics of the material that the current is flowing through. The material can resist the flow of the charges, and the measure of how much a material resists the flow of charges is known as the resistivity. This resistivity is crudely analogous to the friction between two materials that resists motion.

Resistivity

When a voltage is applied to a conductor, an electrical field is created, and charges in the conductor feel a force due to the electrical field. The current density that results depends on the electrical field and the properties of the material. This dependence can be very complex. In some materials, including metals at a given temperature, the current density is approximately proportional to the electrical field. In these cases, the current density can be modeled as

where is the electrical conductivity. The electrical conductivity is analogous to thermal conductivity and is a measure of a material’s ability to conduct or transmit electricity. Conductors have a higher electrical conductivity than insulators. Since the electrical conductivity is , the units are

Here, we define a unit named the ohm with the Greek symbol uppercase omega, . The unit is named after Georg Simon Ohm, whom we will discuss later in this chapter. The is used to avoid confusion with the number 0. One ohm equals one volt per amp: . The units of electrical conductivity are therefore .

Conductivity is an intrinsic property of a material. Another intrinsic property of a material is the resistivity, or electrical resistivity. The resistivity of a material is a measure of how strongly a material opposes the flow of electrical current. The symbol for resistivity is the lowercase Greek letter rho, , and resistivity is the reciprocal of electrical conductivity:

The unit of resistivity in SI units is the ohm-meter . We can define the resistivity in terms of the electrical field and the current density,

The greater the resistivity, the larger the field needed to produce a given current density. The lower the resistivity, the larger the current density produced by a given electrical field. Good conductors have a high conductivity and low resistivity. Good insulators have a low conductivity and a high resistivity. Table 9.1 lists resistivity and conductivity values for various materials.

| Material | Conductivity, |

Resistivity, |

Temperature Coefficient, |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductors | |||

| Silver | 0.0038 | ||

| Copper | 0.0039 | ||

| Gold | 0.0034 | ||

| Aluminum | 0.0039 | ||

| Tungsten | 0.0045 | ||

| Iron | 0.0065 | ||

| Platinum | 0.0039 | ||

| Steel | |||

| Lead | |||

| Manganin (Cu, Mn, Ni alloy) | 0.000002 | ||

| Constantan (Cu, Ni alloy) | 0.00003 | ||

| Mercury | 0.0009 | ||

| Nichrome (Ni, Fe, Cr alloy) | 0.0004 | ||

| Semiconductors[1] | |||

| Carbon (pure) | −0.0005 | ||

| Carbon | −0.0005 | ||

| Germanium (pure) | −0.048 | ||

| Germanium | −0.050 | ||

| Silicon (pure) | 2300 | −0.075 | |

| Silicon | −0.07 | ||

| Insulators | |||

| Amber | |||

| Glass | |||

| Lucite | |||

| Mica | |||

| Quartz (fused) | |||

| Rubber (hard) | |||

| Sulfur | |||

| TeflonTM | |||

| Wood |

The materials listed in the table are separated into categories of conductors, semiconductors, and insulators, based on broad groupings of resistivity. Conductors have the smallest resistivity, and insulators have the largest; semiconductors have intermediate resistivity. Conductors have varying but large, free charge densities, whereas most charges in insulators are bound to atoms and are not free to move. Semiconductors are intermediate, having far fewer free charges than conductors, but having properties that make the number of free charges depend strongly on the type and amount of impurities in the semiconductor. These unique properties of semiconductors are put to use in modern electronics, as we will explore in later chapters.

Check Your Understanding 9.5

Copper wires are routinely used for extension cords and house wiring for several reasons. Copper has the highest electrical conductivity rating, and therefore the lowest resistivity rating, of all nonprecious metals. Also important is the tensile strength, where the tensile strength is a measure of the force required to pull an object to the point where it breaks. The tensile strength of a material is the maximum amount of tensile stress it can take before breaking. Copper has a high tensile strength, . A third important characteristic is ductility. Ductility is a measure of a material’s ability to be drawn into wires and a measure of the flexibility of the material, and copper has a high ductility. Summarizing, for a conductor to be a suitable candidate for making wire, there are at least three important characteristics: low resistivity, high tensile strength, and high ductility. What other materials are used for wiring and what are the advantages and disadvantages?

Temperature Dependence of Resistivity

Looking back at Table 9.1, you will see a column labeled “Temperature Coefficient.” The resistivity of some materials has a strong temperature dependence. In some materials, such as copper, the resistivity increases with increasing temperature. In fact, in most conducting metals, the resistivity increases with increasing temperature. The increasing temperature causes increased vibrations of the atoms in the lattice structure of the metals, which impede the motion of the electrons. In other materials, such as carbon, the resistivity decreases with increasing temperature. In many materials, the dependence is approximately linear and can be modeled using a linear equation:

where is the resistivity of the material at temperature T, is the temperature coefficient of the material, and is the resistivity at , usually taken as .

Note also that the temperature coefficient is negative for the semiconductors listed in Table 9.1, meaning that their resistivity decreases with increasing temperature. They become better conductors at higher temperature, because increased thermal agitation increases the number of free charges available to carry current. This property of decreasing with temperature is also related to the type and amount of impurities present in the semiconductors.

Resistance

We now consider the resistance of a wire or component. The resistance is a measure of how difficult it is to pass current through a wire or component. Resistance depends on the resistivity. The resistivity is a characteristic of the material used to fabricate a wire or other electrical component, whereas the resistance is a characteristic of the wire or component.

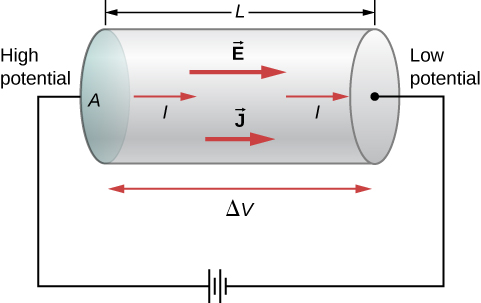

To calculate the resistance, consider a section of conducting wire with cross-sectional area A, length L, and resistivity A battery is connected across the conductor, providing a potential difference across it (Figure 9.13). The potential difference produces an electrical field that is proportional to the current density, according to .

The magnitude of the electrical field across the segment of the conductor is equal to the voltage divided by the length, , and the magnitude of the current density is equal to the current divided by the cross-sectional area, As with capacitance, we use V to represent the potential difference ΔV across the resistor. Using this information and recalling that the electrical field is proportional to the resistivity and the current density, we can see that the voltage is proportional to the current:

Resistance

The ratio of the voltage to the current is defined as the resistance R:

The resistance of a cylindrical segment of a conductor is equal to the resistivity of the material times the length divided by the area:

The unit of resistance is the ohm, . For a given voltage, the higher the resistance, the lower the current.

Resistors

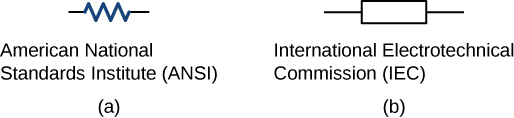

A common component in electronic circuits is the resistor. The resistor can be used to reduce current flow or provide a voltage drop. Figure 9.14 shows the symbols used for a resistor in schematic diagrams of a circuit. Two commonly used standards for circuit diagrams are provided by the American National Standard Institute (ANSI, pronounced “AN-see”) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). Both systems are commonly used. We use the ANSI standard in this text for its visual recognition, but we note that for larger, more complex circuits, the IEC standard may have a cleaner presentation, making it easier to read.

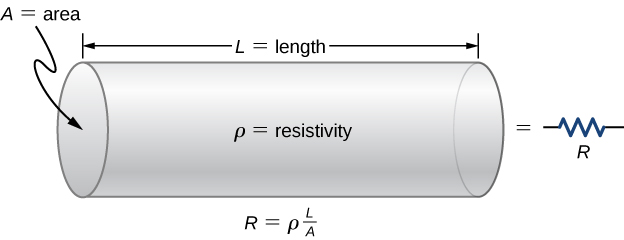

Material and shape dependence of resistance

A resistor can be modeled as a cylinder with a cross-sectional area A and a length L, made of a material with a resistivity (Figure 9.15). The resistance of the resistor is .

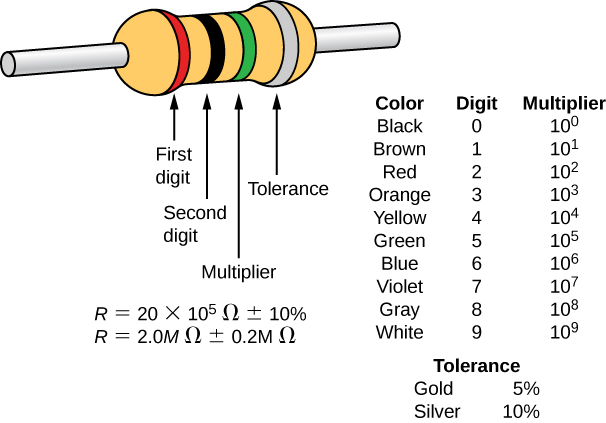

The most common material used to make a resistor is carbon. A carbon track is wrapped around a ceramic core, and two copper leads are attached. A second type of resistor is the metal film resistor, which also has a ceramic core. The track is made from a metal oxide material, which has semiconductive properties similar to carbon. Again, copper leads are inserted into the ends of the resistor. The resistor is then painted and marked for identification. A resistor has four colored bands, as shown in Figure 9.16.

Resistances range over many orders of magnitude. Some ceramic insulators, such as those used to support power lines, have resistances of or more. A dry person may have a hand-to-foot resistance of , whereas the resistance of the human heart is about . A meter-long piece of large-diameter copper wire may have a resistance of , and superconductors have no resistance at all at low temperatures. As we have seen, resistance is related to the shape of an object and the material of which it is composed.

Example 9.5

Current Density, Resistance, and Electrical field for a Current-Carrying Wire

Calculate the current density, resistance, and electrical field of a 5-m length of copper wire with a diameter of 2.053 mm (12-gauge) carrying a current of .Strategy

We can calculate the current density by first finding the cross-sectional area of the wire, which is and the definition of current density . The resistance can be found using the length of the wire , the area, and the resistivity of copper , where . The resistivity and current density can be used to find the electrical field.Solution

First, we calculate the current density:The resistance of the wire is

Finally, we can find the electrical field:

Significance

From these results, it is not surprising that copper is used for wires for carrying current because the resistance is quite small. Note that the current density and electrical field are independent of the length of the wire, but the voltage depends on the length.Interactive

Engage the simulation below to see what the effects of the cross-sectional area, the length, and the resistivity of a wire are on the resistance of a conductor. Adjust the variables using slide bars and see if the resistance becomes smaller or larger.

The resistance of an object also depends on temperature, since is directly proportional to For a cylinder, we know , so if L and A do not change greatly with temperature, R has the same temperature dependence as (Examination of the coefficients of linear expansion shows them to be about two orders of magnitude less than typical temperature coefficients of resistivity, so the effect of temperature on L and A is about two orders of magnitude less than on Thus,

is the temperature dependence of the resistance of an object, where is the original resistance (usually taken to be and R is the resistance after a temperature change The color code gives the resistance of the resistor at a temperature of .

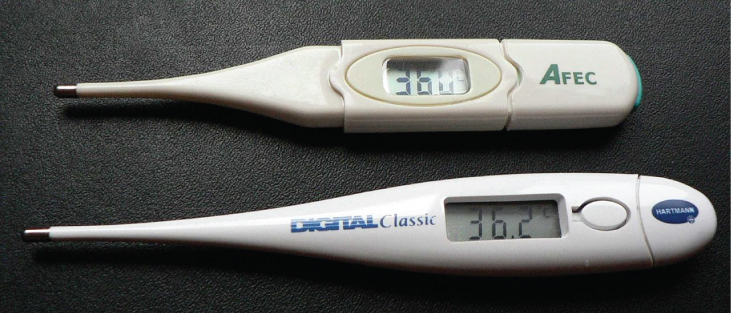

Numerous thermometers are based on the effect of temperature on resistance (Figure 9.17). One of the most common thermometers is based on the thermistor, a semiconductor crystal with a strong temperature dependence, the resistance of which is measured to obtain its temperature. The device is small, so that it quickly comes into thermal equilibrium with the part of a person it touches.

Example 9.6

Calculating Resistance

Although caution must be used in applying and for temperature changes greater than , for tungsten, the equations work reasonably well for very large temperature changes. A tungsten filament at has a resistance of . What would the resistance be if the temperature is increased to ?Strategy

This is a straightforward application of , since the original resistance of the filament is given as and the temperature change is .Solution

The resistance of the hotter filament R is obtained by entering known values into the above equation:Significance

Notice that the resistance changes by more than a factor of 10 as the filament warms to the high temperature and the current through the filament depends on the resistance of the filament and the voltage applied. If the filament is used in an incandescent light bulb, the initial current through the filament when the bulb is first energized will be higher than the current after the filament reaches the operating temperature.Check Your Understanding 9.6

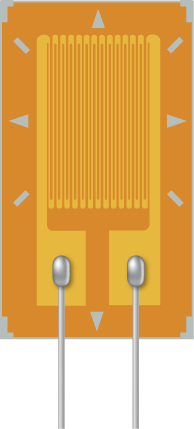

A strain gauge is an electrical device to measure strain, as shown below. It consists of a flexible, insulating backing that supports a conduction foil pattern. The resistance of the foil changes as the backing is stretched. How does the strain gauge resistance change? Is the strain gauge affected by temperature changes?

Example 9.7

The Resistance of Coaxial Cable

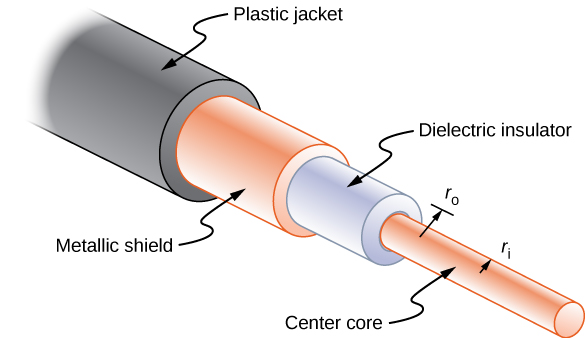

Long cables can sometimes act like antennas, picking up electronic noise, which are signals from other equipment and appliances. Coaxial cables are used for many applications that require this noise to be eliminated. For example, they can be found in the home in cable TV connections or other audiovisual connections. Coaxial cables consist of an inner conductor of radius surrounded by a second, outer concentric conductor with radius (Figure 9.18). The space between the two is normally filled with an insulator such as polyethylene plastic. A small amount of radial leakage current occurs between the two conductors. Determine the resistance of a coaxial cable of length L.

Strategy

We cannot use the equation directly. Instead, we look at concentric cylindrical shells, with thickness dr, and integrate.Solution

We first find an expression for dR and then integrate from to ,Significance

The resistance of a coaxial cable depends on its length, the inner and outer radii, and the resistivity of the material separating the two conductors. Since this resistance is not infinite, a small leakage current occurs between the two conductors. This leakage current leads to the attenuation (or weakening) of the signal being sent through the cable.Check Your Understanding 9.7

The resistance between the two conductors of a coaxial cable depends on the resistivity of the material separating the two conductors, the length of the cable and the inner and outer radius of the two conductor. If you are designing a coaxial cable, how does the resistance between the two conductors depend on these variables?

Interactive

View this simulation to see how the voltage applied and the resistance of the material the current flows through affects the current through the material. You can visualize the collisions of the electrons and the atoms of the material effect the temperature of the material.