10.6 Nuclear Fusion

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the process of nuclear fusion in terms of its product and reactants

- Calculate the energies of particles produced by a fusion reaction

- Explain the fission concept in the context of fusion bombs, the production of energy by the Sun, and nucleosynthesis

The process of combining lighter nuclei to make heavier nuclei is called nuclear fusion. As with fission reactions, fusion reactions are exothermic—they release energy. Suppose that we fuse a carbon and helium nuclei to produce oxygen:

The energy changes in this reaction can be understood using a graph of binding energy per nucleon (Figure 10.7). Comparing the binding energy per nucleon for oxygen, carbon, and helium, the oxygen nucleus is much more tightly bound than the carbon and helium nuclei, indicating that the reaction produces a drop in the energy of the system. This energy is released in the form of gamma radiation. Fusion reactions are said to be exothermic when the amount of energy released (known as the Q value) in each reaction is greater than zero

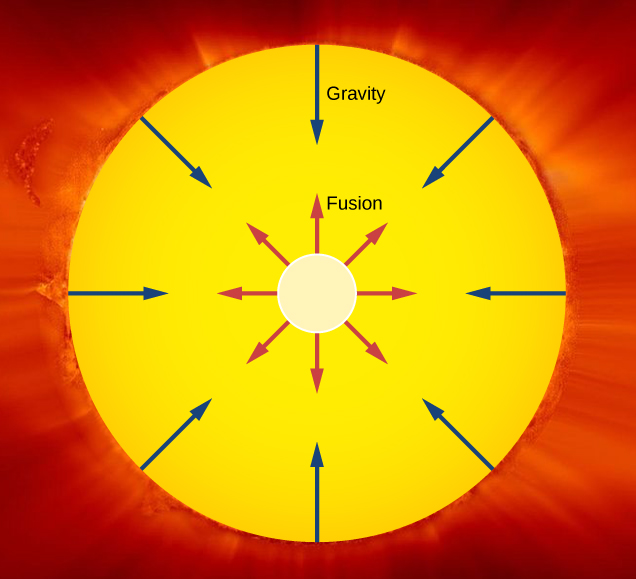

An important example of nuclear fusion in nature is the production of energy in the Sun. In 1938, Hans Bethe proposed that the Sun produces energy when hydrogen nuclei () fuse into stable helium nuclei in the Sun’s core (Figure 10.22). This process, called the proton-proton chain, is summarized by three reactions:

Thus, a stable helium nucleus is formed from the fusion of the nuclei of the hydrogen atom. These three reactions can be summarized by

The net Q value is about 26 MeV. The release of this energy produces an outward thermal gas pressure that prevents the Sun from gravitational collapse. Astrophysicists find that hydrogen fusion supplies the energy stars require to maintain energy balance over most of a star's life span.

Nucleosynthesis

Scientist now believe that many heavy elements found on Earth and throughout the universe were originally synthesized by fusion within the hot cores of the stars. This process is known as nucleosynthesis. For example, in lighter stars, hydrogen combines to form helium through the proton-proton chain. Once the hydrogen fuel is exhausted, the star enters the next stage of its life and fuses helium. An example of a nuclear reaction chain that can occur is:

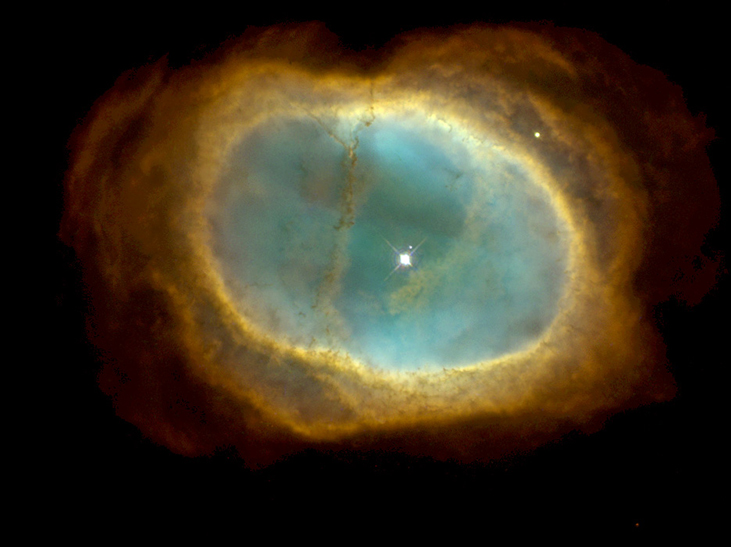

Carbon and oxygen nuclei produced in such processes eventually reach the star’s surface by convection. Near the end of its lifetime, the star loses its outer layers into space, thus enriching the interstellar medium with the nuclei of heavier elements (Figure 10.23).

Stars similar in mass to the Sun do not become hot enough to fuse nuclei as heavy (or heavier) than oxygen nuclei. However, in massive stars whose cores become much hotter even more complex nuclei are produced. Some representative reactions are

Nucleosynthesis continues until the core is primarily iron-nickel metal. Now, iron has the peculiar property that any fusion or fission reaction involving the iron nucleus is endothermic, meaning that energy is absorbed rather than produced. Hence, nuclear energy cannot be generated in an iron-rich core. Lacking an outward pressure from fusion reactions, the star begins to contract due to gravity. This process heats the core to a temperature on the order of Expanding shock waves generated within the star due to the collapse cause the star to quickly explode. The luminosity of the star can increase temporarily to nearly that of an entire galaxy. During this event, the flood of energetic neutrons reacts with iron and the other nuclei to produce elements heavier than iron. These elements, along with much of the star, are ejected into space by the explosion. Supernovae and the formation of planetary nebulas together play a major role in the dispersal of chemical elements into space.

Eventually, much of the material lost by stars is pulled together through the gravitational force, and it condenses into a new generation of stars and accompanying planets. Recent images from the Hubble Space Telescope provide a glimpse of this magnificent process taking place in the constellation Serpens (Figure 10.24). The new generation of stars begins the nucleosynthesis process anew, with a higher percentage of heavier elements. Thus, stars are “factories” for the chemical elements, and many of the atoms in our bodies were once a part of stars.

Example 10.11

Energy of the Sun

The power output of the Sun is approximately Most of this energy is produced in the Sun’s core by the proton-proton chain. This energy is transmitted outward by the processes of convection and radiation. (a) How many of these fusion reactions per second must occur to supply the power radiated by the Sun? (b) What is the rate at which the mass of the Sun decreases? (c) In about five billion years, the central core of the Sun will be depleted of hydrogen. By what percentage will the mass of the Sun have decreased from its present value when the core is depleted of hydrogen?Strategy

The total energy output per second is given in the problem statement. If we know the energy released in each fusion reaction, we can determine the rate of the fusion reactions. If the mass loss per fusion reaction is known, the mass loss rate is known. Multiplying this rate by five billion years gives the total mass lost by the Sun. This value is divided by the original mass of the Sun to determine the percentage of the Sun’s mass that has been lost when the hydrogen fuel is depleted.Solution

- The decrease in mass for the fusion reaction is The energy released per fusion reaction is Thus, to supply there must be

- The Sun’s mass decreases by per fusion reaction, so the rate at which its mass decreases is

- In the Sun’s mass will therefore decrease by The current mass of the Sun is about so the percentage decrease in its mass when its hydrogen fuel is depleted will be

Significance

After five billion years, the Sun is very nearly the same mass as it is now. Hydrogen burning does very little to change the mass of the Sun. This calculation assumes that only the proton-proton decay change is responsible for the power output of the Sun.Check Your Understanding 10.6

Where does the energy from the Sun originate?

The Hydrogen Bomb

In 1942, Robert Oppenheimer suggested that the extremely high temperature of an atomic bomb could be used to trigger a fusion reaction between deuterium and tritium, thus producing a fusion (or hydrogen) bomb. The reaction between deuterium and tritium, both isotopes of hydrogen, is given by

Deuterium is relatively abundant in ocean water but tritium is scarce. However, tritium can be generated in a nuclear reactor through a reaction involving lithium. The neutrons from the reactor cause the reaction

to produce the desired tritium. The first hydrogen bomb was detonated in 1952 on the remote island of Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands. A hydrogen bomb has never been used in war. Modern hydrogen bombs are approximately 1000 times more powerful than the fission bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II.

The Fusion Reactor

The fusion chain believed to be the most practical for use in a nuclear fusion reactor is the following two-step process:

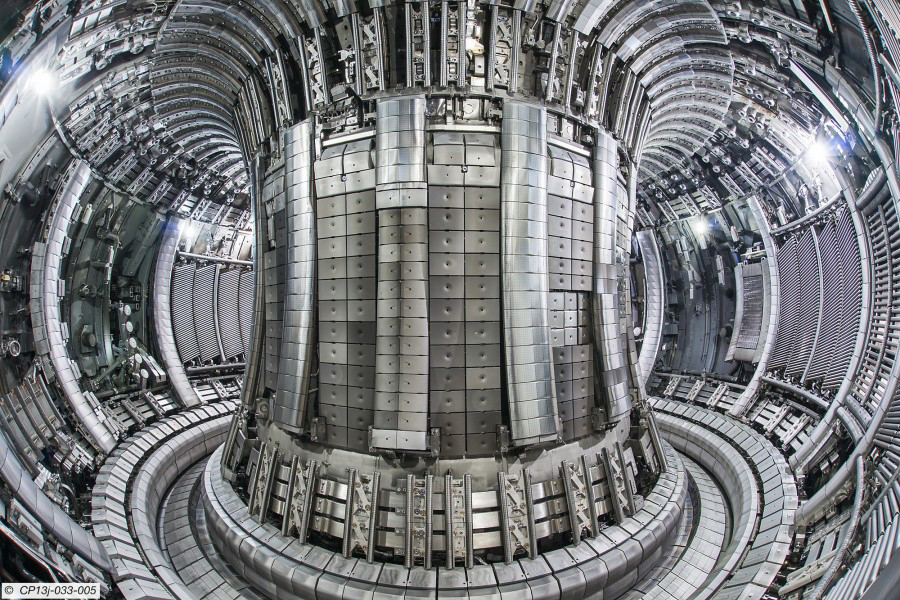

This chain, like the proton-proton chain, produces energy without any radioactive by-product. However, there is a very difficult problem that must be overcome before fusion can be used to produce significant amounts of energy: Extremely high temperatures are needed to drive the fusion process. To meet this challenge, test fusion reactors are being developed to withstand temperatures 20 times greater than the Sun’s core temperature. An example is the Joint European Torus (JET) shown in Figure 10.25. A great deal of work still has to be done on fusion reactor technology, but many scientists predict that fusion energy will power the world’s cities by the end of the twenty-first century.