9.1 Linear Momentum

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain what momentum is, physically

- Calculate the momentum of a moving object

Our study of kinetic energy showed that a complete understanding of an object’s motion must include both its mass and its velocity (). However, as powerful as this concept is, it does not include any information about the direction of the moving object’s velocity vector. We’ll now define a physical quantity that includes direction.

Like kinetic energy, this quantity includes both mass and velocity; like kinetic energy, it is a way of characterizing the “quantity of motion” of an object. It is given the name momentum (from the Latin word movimentum, meaning “movement”), and it is represented by the symbol p.

Momentum

The momentum p of an object is the product of its mass and its velocity:

As shown in Figure 9.2, momentum is a vector quantity (since velocity is). This is one of the things that makes momentum useful and not a duplication of kinetic energy. It is perhaps most useful when determining whether an object’s motion is difficult to change (Figure 9.3) or easy to change (Figure 9.4) over a short time interval.

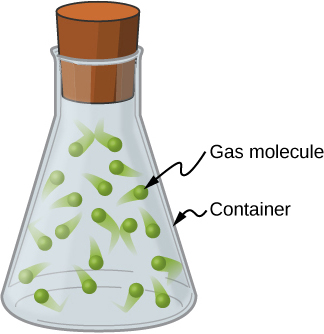

Unlike kinetic energy, momentum depends equally on an object’s mass and velocity. For example, as you will learn when you study thermodynamics, the average speed of an air molecule at room temperature is approximately 500 m/s, with an average molecular mass of ; its momentum is thus

For comparison, a typical automobile might have a speed of only 15 m/s, but a mass of 1400 kg, giving it a momentum of

These momenta are different by 27 orders of magnitude, or a factor of a billion billion billion!