15.4 Pendulums

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- State the forces that act on a simple pendulum

- Determine the angular frequency, frequency, and period of a simple pendulum in terms of the length of the pendulum and the acceleration due to gravity

- Define the period for a physical pendulum

- Define the period for a torsional pendulum

Pendulums are in common usage. Grandfather clocks use a pendulum to keep time and a pendulum can be used to measure the acceleration due to gravity. For small displacements, a pendulum is a simple harmonic oscillator.

The Simple Pendulum

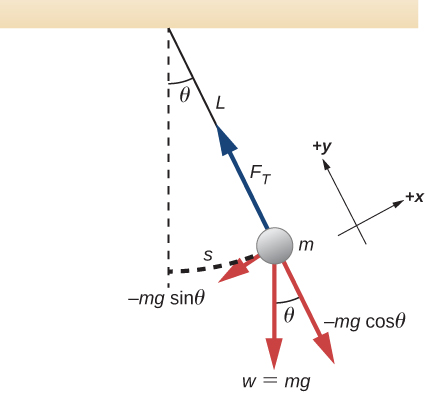

A simple pendulum is defined to have a point mass, also known as the pendulum bob, which is suspended from a string of length L with negligible mass (Figure 15.20). Here, the only forces acting on the bob are the force of gravity (i.e., the weight of the bob) and tension from the string. The mass of the string is assumed to be negligible as compared to the mass of the bob.

Consider the torque on the pendulum. The force providing the restoring torque is the component of the weight of the pendulum bob that acts along the arc length. The torque is the length of the string L times the component of the net force that is perpendicular to the radius of the arc. The minus sign indicates the torque acts in the opposite direction of the angular displacement:

The solution to this differential equation involves advanced calculus, and is beyond the scope of this text. But note that for small angles (less than 15 degrees or about 0.26 radians), and differ by less than 1%, if θ is measured in radians. We can then use the small angle approximation The angle describes the position of the pendulum. Using the small angle approximation gives an approximate solution for small angles,

Because this equation has the same form as the equation for SHM, the solution is easy to find. The angular frequency is

and the period is

The period of a simple pendulum depends on its length and the acceleration due to gravity. The period is completely independent of other factors, such as mass and the maximum displacement. As with simple harmonic oscillators, the period T for a pendulum is nearly independent of amplitude, especially if is less than about Even simple pendulum clocks can be finely adjusted and remain accurate.

Note the dependence of T on g. If the length of a pendulum is precisely known, it can actually be used to measure the acceleration due to gravity, as in the following example.

Example 15.3

Measuring Acceleration due to Gravity by the Period of a Pendulum

What is the acceleration due to gravity in a region where a simple pendulum having a length 75.000 cm has a period of 1.7357 s?Strategy

We are asked to find g given the period T and the length L of a pendulum. We can solve for g, assuming only that the angle of deflection is less than .Solution

- Square and solve for g:

- Substitute known values into the new equation:

- Calculate to find g:

Significance

This method for determining g can be very accurate, which is why length and period are given to five digits in this example. For the precision of the approximation to be better than the precision of the pendulum length and period, the maximum displacement angle should be kept below about .Check Your Understanding 15.4

An engineer builds two simple pendulums. Both are suspended from small wires secured to the ceiling of a room. Each pendulum hovers 2 cm above the floor. Pendulum 1 has a bob with a mass of 10 kg. Pendulum 2 has a bob with a mass of 100 kg. Describe how the motion of the pendulums will differ if the bobs are both displaced by .

Physical Pendulum

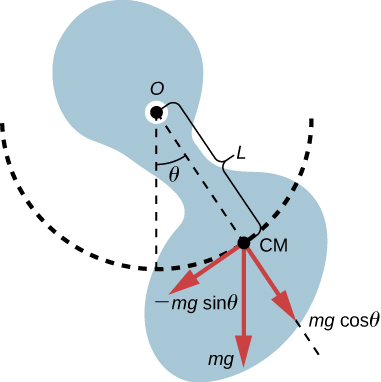

Any object can oscillate like a pendulum. Consider a coffee mug hanging on a hook in the pantry. If the mug gets knocked, it oscillates back and forth like a pendulum until the oscillations die out. We have described a simple pendulum as a point mass and a string. A physical pendulum is any object whose oscillations are similar to those of the simple pendulum, but cannot be modeled as a point mass on a string, and the mass distribution must be included into the equation of motion.

As for the simple pendulum, the restoring force of the physical pendulum is the force of gravity. With the simple pendulum, the force of gravity acts on the center of the pendulum bob. In the case of the physical pendulum, the force of gravity acts on the center of mass (CM) of an object. The object oscillates about a point O. Consider an object of a generic shape as shown in Figure 15.21.

When a physical pendulum is hanging from a point but is free to rotate, it rotates because of the torque applied at the CM, produced by the component of the object’s weight that acts tangent to the motion of the CM. Taking the counterclockwise direction to be positive, the component of the gravitational force that acts tangent to the motion is . The minus sign is the result of the restoring force acting in the opposite direction of the increasing angle. Recall that the torque is equal to . The magnitude of the torque is equal to the length of the radius arm times the tangential component of the force applied, . Here, the length L of the radius arm is the distance between the point of rotation and the CM. To analyze the motion, start with the net torque. Like the simple pendulum, consider only small angles so that . Recall from Fixed-Axis Rotation on rotation that the net torque is equal to the moment of inertia times the angular acceleration where :

Using the small angle approximation and rearranging:

Once again, the equation says that the second time derivative of the position (in this case, the angle) equals minus a constant times the position. The solution is

where is the maximum angular displacement. The angular frequency is

The period is therefore

Note that for a simple pendulum, the moment of inertia is and the period reduces to .

Example 15.4

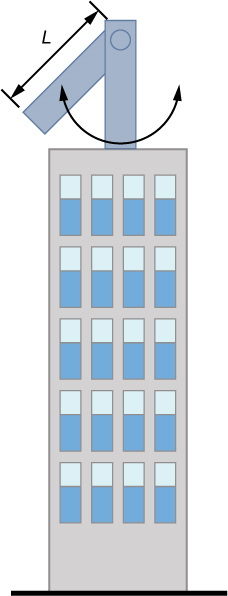

Reducing the Swaying of a Skyscraper

In extreme conditions, skyscrapers can sway up to two meters with a frequency of up to 20.00 Hz due to high winds or seismic activity. Several companies have developed physical pendulums that are placed on the top of the skyscrapers. As the skyscraper sways to the right, the pendulum swings to the left, reducing the sway. Assuming the oscillations have a frequency of 0.50 Hz, design a pendulum that consists of a long beam, of constant density, with a mass of 100 metric tons and a pivot point at one end of the beam. What should be the length of the beam?

Strategy

We are asked to find the length of the physical pendulum with a known mass. We first need to find the moment of inertia of the beam. We can then use the equation for the period of a physical pendulum to find the length.Solution

- Find the moment of inertia for the CM:

Use the parallel axis theorem to find the moment of inertia about the point of rotation for a rod length L:

- The period of a physical pendulum with its center of mass a distance l from the pivot point has a period of . In this problem, L has been defined as the total length of the rod, so . Use the moment of inertia to solve for the length L:

Significance

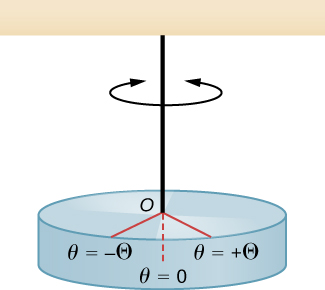

There are many ways to reduce the oscillations, including modifying the shape of the skyscrapers, using multiple physical pendulums, and using tuned-mass dampers.Torsional Pendulum

A torsional pendulum consists of a rigid body suspended by a light wire or spring (Figure 15.22). When the body is twisted some small maximum angle and released from rest, the body oscillates between and . The restoring torque is supplied by the shearing of the string or wire.

The restoring torque can be modeled as being proportional to the angle:

The variable kappa is known as the torsion constant of the wire or string. The minus sign shows that the restoring torque acts in the opposite direction to increasing angular displacement. The net torque is equal to the moment of inertia times the angular acceleration:

This equation says that the second time derivative of the position (in this case, the angle) equals a negative constant times the position. This looks very similar to the equation of motion for the SHM , where the period was found to be . Therefore, the period of the torsional pendulum can be found using

The units for the torsion constant are and the units for the moment of inertial are which show that the unit for the period is the second.

Example 15.5

Measuring the Torsion Constant of a String

A rod has a length of and a mass of 4.00 kg. A string is attached to the CM of the rod and the system is hung from the ceiling (Figure 15.23). The rod is displaced 10 degrees from the equilibrium position and released from rest. The rod oscillates with a period of 0.5 s. What is the torsion constant ?

Strategy

We are asked to find the torsion constant of the string. We first need to find the moment of inertia.Solution

- Find the moment of inertia for the CM:

- Calculate the torsion constant using the equation for the period: